Image

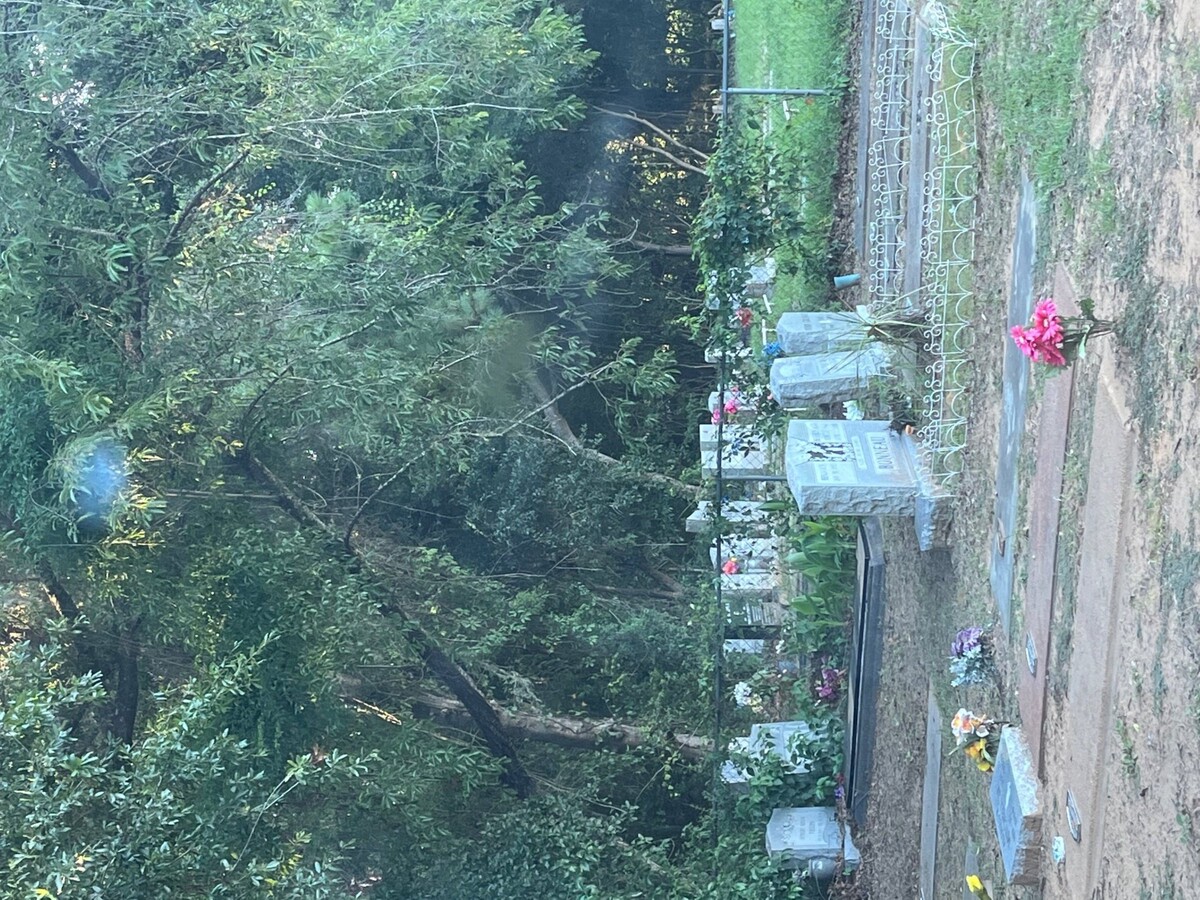

Black burial grounds in Charleston, South Carolina, will soon receive the long-overdue care and protection that they need. My best friend lives on Johns Island and yesterday he gave me a tour of his family burial grounds. Both of these pictures were captured yesterday. Appreciate you sharing the sacred history of your family that spans many generations.

Shoutout Mr. Saleem Munir.

The Preservation Society of Charleston has been awarded a $50,000 grant to launch its “Mapping Charleston’s Black Burial Grounds” initiative, The Post and Courier reported Saturday. The African American Civil Rights Preservation Grant, courtesy of the National Park Service, aims to produce a comprehensive inventory of the lost and overlooked Black burial grounds within the city.

There are many Black cemeteries scattered throughout Charleston, and the Heriot Street cemetery, in particular, holds the remains of more than 2,000 African Americans buried there between 1865 and 1965. According to The Post and Courier, many burial grounds “have been paved over, built upon, dug up, obscured or belittled by unscrupulous developers and those who stand to gain something at the expense of the dead.”

The Preservation Society of Charleston plans to create a centralized database of burial sites that deserve protection.

Per the PSC, “each burial site is a significant place of remembrance that conveys important truths of the American story and the stories of those who built our city. Yet because these sites are underrepresented in traditional historic surveys and, in many cases, undocumented, they are highly vulnerable to development pressures. Due to recent, unprecedented growth, Charleston is now challenged to recognize and ensure protections for these sites before they are lost.”

The Daniel Island News wrote last week that in her letter of support for PSC’s grant application, Dr. Tonya M. Matthews, president and CEO of the International African American Museum, maintained that the museum shared “the PSC’s vision to create strategy and structure to engage community such that members of Charleston’s African American communities are not only beneficiaries of this project, but creators and drivers of it.”

The city previously made efforts to protect cemeteries from being desecrated or destroyed via the gravesite protection ordinance that was passed last September.

The main goals of the PSC’s two-year project are to determine the boundaries and contents of Black burial grounds so the city can use the data as a planning and preservation tool.

“We cannot understate the significance of this award and extend a heartfelt congratulations to the Preservation Society of Charleston on this momentous achievement,” said Jessica Knuff, president of the Daniel Island Historical Society.

“We look forward to the important work that will be done to document and study these sacred burial grounds — not only on the Cainhoy peninsula, but all across the Charleston region,” Knuff added. “Those laid to rest in these hallowed places are worthy of our attention and our respect. May this critical work shine a spotlight on their final resting places, many of them long forgotten and hidden, and give them the protection they so rightly deserve.”

“Together we recognize the urgent need for more data and information about African American burial sites to help inform land-use planning so as to avoid harmful impacts to gravesites, especially those which are unmarked,” Mayor John Tecklenburg wrote in a letter of support that accompanied the grant application.

Preservation Society President and CEO Brian Turner said the NPS grant will be beneficial to city officials and preservationists to help “flag development proposals that could impact known cemeteries.”

The PSC’s efforts continue the work of Dr. Ade Ofunniyin, the late anthropologist, College of Charleston adjunct professor, and founder of The Gullah Society, who died in 2020.

Turner said he hopes the cemetery-mapping project leads to a larger community-driven effort to document the contributions of Black people in the region.

“Fundamentally, community engagement has to be part of the process,” Turner said. “We would be irresponsible if we didn’t lead with community dialogue to discern what the community wants.”